One of the most beautiful Greek myths, which fascinated Carl Gustav Jung because of its alchemical underpinnings, is the story of Cadmus and Harmony. It is beautifully retold in The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony by Roberto Calasso, who begins the story in this way:

“Zeus was seducing the Nymph Pluto when Ge, avenger of all the victims of the Olympian age, nodded to her son Typhon, as one assassin giving the go-ahead to another. A huge body stretched across heaven and earth: an arm, one of the two hundred attached to that body, reached out to Olympus, the fingers searching behind a rock from which rose rags of smoke. Typhon’s hand closed around Zeus’s bundle of thunderbolts. The sovereign god had lost his weapon. Olympus was terror-struck. The gods fled like a stampeding herd. They shed the human forms that made them too recognizable and unique. Trembling, they camouflaged themselves beneath animal skins: ibis, jackals, dogs. And they flew toward Egypt, where they would be able to blend in among the hundreds and thousands of other ibis, jackals, and dogs, the motionless, painted guardians of tombs and temples.”

Typhon fighting with Zeus

Gaia (Ge) had lost her patience with Zeus. His constant raping and seductive escapades had brought chaos and destruction. At Gaia’s behest Typhon had robbed Zeus of the insignia of his power. The universe had returned to the primordial state of being ruled by rampant instincts.

Rembrandt van Rijn, “The Abduction of Europa”

Shortly before Typhon captured him, Zeus had completed another significant conquest – that of Europa. He beguiled her in the guise of a white bull. The historian Norman Davies claims that there are many important connotations to this story of abduction. By bringing Europa from Phoenicia to Crete Zeus was “transferring the fruits of the older Asian civilizations of the East to the new island colonies of the Aegean.” Phoenicia was linked to Egypt, and consequently the ride of Zeus and Europa provided a link between Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece. It is important to note that the Greeks, unlike the Egyptians, were a mentally restless nation, keen to travel to distant shores and experience other cultures. The greatest Greek heroes, such as Odysseus and Cadmus (Europa’s brother sent by his father to look for her) were incorrigible travelers, endlessly curious and weary globetrotters. The name Cadmus may possibly mean “the one who comes from the East,” though this has not been established with certainty. Nevertheless, he epitomizes a migrant, an outsider, an alien.

While looking for Europa Cadmus rescued Zeus from the clutches of Typhon. In a masterful rendering of Calasso:

“Olympus was uninhabited now, a museum in the night. And in a cave a few yards from Cadmus, although he hadn’t found the place yet, lay Zeus, helpless. Wrapping himself around the god’s body, Typhon had managed to wrench his adamantine sickle from him and had cut through the sinews of his hands and feet. Now, drawn out from his body, Zeus’s sinews formed a bundle of dark, shiny stalks, not unlike the bundle of lightning bolts that lay beside them, although these were bright and smoking. Zeus’s body could just be glimpsed through the shadows, an abandoned sack. Wrapped in a bearskin, his sinews were being guarded by Delphine, half girl, half snake. And out from the cave drifted the breath of Typhon’s many mouths, Typhon with his hundred animal heads and the thousands of snakes that framed them.”

The mighty Zeus was reduced to a heap of meat, unable to stand proudly erect. It seemed that Zeus’s lower spineless, snakelike nature had taken over and he had been reduced to a beast. Cadmus happened upon this show of helplessness:

“Cadmus had no weapons, bar the invisible resources of his mind. He remembered how in his childhood, when he used to follow his father on his travels, the priests of the Egyptian temples had squeezed into his mouth ‘the ineffable milk of books.’ And he remembered the most intense joy he had ever known: one day Apollo had revealed to him, and him alone, ‘the just music.’ … Cadmus decided to play it to the monster now, a last voice from the deserted world of the gods. Hiding in a thicket of trees, he played his pipes. The notes penetrated Typhon’s cave, rousing him from his happy torpor. Then Cadmus saw some of Typhon’s arms slithering toward him. Head after head rose before him, until the only human one among them spoke to him in a friendly voice. Typhon invited Cadmus to compete with him: pipes versus thunder. He spoke like a bandit in need of company who grabs at the first chance to show off his power. With the bluster of the braggart, he promised him marvelous things, although in this particular moment that braggart really was the sole master of the cosmos. And, as he spoke, he was struggling to imitate Zeus, who he had long observed with resentment. He told Cadmus he would take him up to Olympus. He would grant him Athena’s body, untouched. And if he didn’t like Athena he could have Artemis, or Aphrodite, or Hebe. Only Hera was out of bounds, because she belonged to him, the new sovereign. Never had anyone been at once so ridiculous and so powerful.

Cadmus contrived to look serious and respectful, but not frightened. He said it was pointless him trying to compete with his pipes. But with a lyre, maybe. He made up a story of his once having competed with Apollo. And said that, to save his son the embarrassment of being beaten, Zeus had burned his strings to ashes. If only he had some good, tough sinews to make himself a new instrument! With the music of his lyre, Cadmus said, he would be able to stop the planets in their courses and enchant the wild beasts. These words convinced the ingenuous monster, who enjoyed conversation only when it centered on power, immense power, the one thing he was interested in.”

Hendrick Goltzius, Cadmus slaying the Dragon

Cadmus, as a Mercurius figure, set out to outsmart the beast with his trickster ploys. The mind confronted chaos and was victorious, if only for a moment, for the forces of chaos can only be momentarily contained, but never fully overcome. Having recovered Zeus’s sinews, Cadmus started playing the lyre, the tones and harmony of which mesmerized the beast. Zeus used the opportunity to sneak out of the cave. Zeus saw a potential in Cadmus of bringing harmony back to the universe. He promised Cadmus a wife – a woman named Harmonia, who was the daughter of Ares and Aphrodite, though raised by Electra, one of the Pleiades. But first Zeus, inspired by the oracle of Delphi, sent Cadmus on a quest. The oracle had commanded Cadmus to “follow a cow, with moon markings on both her sides, until she lay down, and there to found the city of Thebes.” (Jung, par. 85). Upon finding the right spot for his city Cadmus and his companions were attacked by a snake – son of Ares. Cadmus slayed the best and from its teeth the inhabitants of Thebes sprung up. Calasso continues:

“Now Cadmus must found his city. In the center he would put Harmony’s bed. And around it, everything would be modeled on the geometry of the heavens. Iron bit into soil, the reference points were calculated. Stones of different colors, like the signatures of the planets, were taken from the mountains of Cithaeron, Helicon, and Teumesus, and arranged in piles. The seven gates of the city were laid out to correspond to the seven heavens, and each one was dedicated to a god. Cadmus looked on his finished city as though it were a new toy and decided that their wedding could now go ahead.”

Thebes was an extremely significant cultural and military centre of the Ancient Greece. It gave the world Dionysos and Heracles, as well as Tiresias (the blind seer) and Oedipus. It competed with Athens for power and influence. A significant chapter of the city’s complicated history was its dramatic destruction at the hand of Alexander the Great, who divided up its territory among the enemies of Thebes and sold the inhabitants to slavery. But before that calamity happened, at the mythical beginning, Thebes was a scene of a spectacular wedding to which all the gods were invited:

“Finally the bridal pair arrived, standing straight as statues on a chariot drawn by a lion and a boar. Apollo played the cithara beside the chariot. No one was surprised to see those unusual animals: wasn’t that what Harmony meant, yoking together the opposite and the wild?”

For a fleeting moment opposites were in harmony. Says Jung (par. 87):

“Out of the hostility of the elements there arises the bond of friendship between them, sealed in the stone, and this bond guarantees the indissolubility and incorruptibility of the lapis. This piece of alchemical logic is borne out by the fact that, according to the myth, Cadmus and Harmonia turned to stone (evidently because of an embarras de richesse: perfect harmony is a dead end). In another version, they turn into snakes, ‘and even into a basilisk,’ Dom Pernety remarks, ‘for the end-product of the work, incorporated with its like, acquires the power ascribed to the basilisk, so the philosophers say.’ For this fanciful author Harmonia is naturally the prima materia, and the marriage of Cadmus, which took place with all the gods assisting, is the coniunctio of Sol and Luna, followed by the production of the tincture or lapis.”

Cadmus and Harmonia turning into snakes

Harmony can never last. Either it returns to the original chaos or it turns into a perfect, but cold stone. Little did the newlyweds know that in a near future they will be expelled from their city by Dionysos and will have to recommence their life of wanderers. At the wedding feast, the most special and portent gift was brought by Aphrodite:

“Aphrodite came up to her daughter Harmony and fastened a fated necklace around her neck. Was it the wonderful necklace Hephaestus had wrought to celebrate the birth of Eros, the archer? Or was it the necklace Zeus had given to Europa, when he laid her down beneath a plane tree in Crete? Harmony blushed, right down to her neck, while her skin thrilled under the cold weight of the necklace. It was a snake shot through with stars, a snake with two heads, one at each end, and the heads had their throats wide open, facing each other. Yet the two mouths could never bite each other, for between them, and caught between their teeth, rose two golden eagles with their wings outspread. Slipped into the double throat of the snake, they functioned as a clasp. The stones radiated desire. They were snake, eagle, and star, but they were the sea too, and the light of the stones trembled in the air, as though upon waves. In that necklace cosmos and ornament for once came together.”

Robert Fowler, “The Necklace”

That beautiful necklace, crafted by the wounded and jealous Hephaestus, who felt betrayed by Aphrodite, would generate nothing but disasters and tragedies in the future, though. Calasso goes on:

“When he had married the young Harmony, the opposite extremes of the world had come together in visible accord for one last time. Immediately afterward they had separated, torn apart.”

Indeed, dismemberment, tearing away at the flesh, seemed to connect to all Thebian characters. Cadmus’s grandson Pentheus made a mistake of banning the worship of Dionysos. As a punishment, his flesh was torn by the Maenads, echoing the story of Dionysos and his dismemberment by the Titans. Oedipus plucked his own eyes out when he found out that he had married his own mother.

Pentheus from Pompeii

Calasso wonders:

“What conclusions can we draw? To invite the gods ruins our relationship with them but sets history in motion. A life in which the gods are not invited isn’t worth living.”

Cadmus, equally blessed and cursed by the gods, is reputed to have brought the Greeks the gift of alphabet. As historian Norman Davies wrote:

“The Phoenician alphabet, which Cadmus reputedly brought to Greece, was phonetic but purely consonantal. It is known in its basic form from before 1200 BC, having, like its partner, Hebrew, supplanted the earlier hieroglyphs. A simple system, easily learned by children, it broke the monopoly in arcane writing which had been exercised for millennia by the priestly castes of the previous Middle Eastern civilizations. The names of the letters passed almost unchanged into Greek: aleph (alpha) = ‘ox’; beth (beta) = ‘house; gimel (gamma) = ‘camel’; daleth (delta) =’tent door.’ The old Greek alphabet was produced by adding five vowels to the original sixteen Phoenician consonants. … In due course it became the ancestor of the main branches of European writing – modern Greek, Etruscan, Latin, Glagolitic and Cyrillic.”

While Calasso ends poetically:

“And Thebes was a heap of rubble. But no one could erase those small letters, those fly’s feet that Cadmus the Phoenician had scattered across Greece, where the winds had brought him in his quest for Europa carried off by a bull that rose from the sea.”

The alphabet – whose letters have their roots in the material world (like in the Europa myth – the very beginning, the first letter, is the bull) – could not have been born without strife and suffering. They were the fruit bore by myth opening doors to the rise of human history.

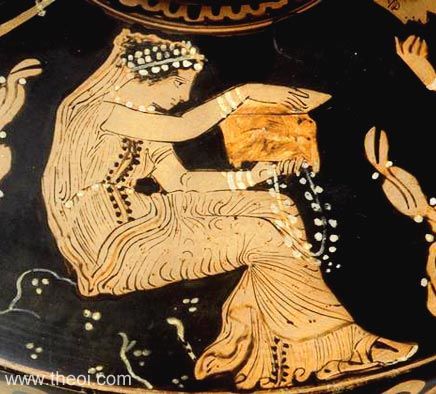

Clio, Muse of history, with box of scrolls

Sources:

Roberto Calasso, The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, Kindle edition

Norman Davies, Europe: A History, Kindle edition

Carl Gustav Jung, Mysterium Coniunctionis, Collected Works 14, Kindle edition

Beautiful, Monika. When I previously wrote about Dionysus and was looking into him, I found his lineage with Cadmus so compelling. Reading your post is a needed spark for prolonged, perhaps endless, contemplation. The line of Cadmus and Harmony bearing the god of drama and dismemberment, the tragedy befalling Cadmus echoing for millennium in the works of bards and poets, their creative will encapsulated in the form of letters. Isn’t it incredible all of these mythic elements swirling around the figure attributed with bringing the Phoenician alphabet to Greece, and it is true there are clear elements of alchemy in the story. Cadmus is Mercurius as you mention, and further so apt that he and his goddess lover, the sol and luna, transform into serpents or dragons. Further that the line of Cadmus came to be so integral in the development of psychoanalysis, depth psychology, and so much modern thought. The necklace given to Harmony is so potent in symbolism and something I feel holds greater meaning than I am grasping in the moment. Yet just along the lines of the wounded Hephaestus being its source, is this not part of the legacy of the alphabet wielded ever since by those suffering the pangs of heartbreak. On a more practical level, with regards to astrology there is the fascinating parallel of the homes of Mercury (Virgo, Gemini) being in polarity to the homes of Jupiter (Pisces, Sagittarius), and there is clear symbolic resonance in this narrative. Also so fitting that Cadmus appears in this pivotal transition point between the Titans unleashing Typhon and the forces of chaos to overwhelm the Olympians and maintain their grasp of power. Cadmus as a figure of Mercury, able to weave chaotic elements into divine musical notes and elegant alphabetic structures. I know we have talked before about dismemberment through Osiris, but isn’t it further interesting how Cadmus who himself I believe had journeyed to Egypt when younger, brought this as well as the alphabet with him from Phoenicia to Greece, and how Harmony seems to have some resonance with Isis.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! So much food for thought in your comment, but this is such an inexhaustible story well. I feel I only stirred the surface a little. The alphabet is not an abstract or disembodied creation. Sure, all the mutable mercurial signs are there in the story, but maybe the whole Zodiac hides in the alphabet, or the totality of the human experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

wonderful analysis Monika! and thank you for this, cause i never heard of that myth before..shame really, i know..haha

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not surprised because it is a lesser known myth but I think really lovely.

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on lampmagician.

LikeLike

Thanks for this Monika 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Have We Had Help? and commented:

If you love Greek Myths, you’ll love this one. 🙂

LikeLike

Great post, Monika. Fascinating connection between the Olympians and the Egyptian gods.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, isn’t the connection fascinating indeed.

Thank you, Jeff.

LikeLike

What a wonderful article.

Thankyou Monika.

Best Wishes,

Hilary

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very very much, Hilary!

LikeLike