John William Waterhouse, “Sleep and His Half Brother Death,” painted after both younger brothers of the painter died of tuberculosis

While the fourteenth century was ravaged by the Black Death, the nineteenth century belonged to tuberculosis, or the White Death, a disease much more insidious and widespread. John Keats died of it at the age of twenty-six, and so did many creative geniuses of the time, such as Friedrich Schiller, Novalis, Emily Brontë, Juliusz Slowacki (a Polish Romantic poet), Frederic Chopin, and countless others. Would Romanticism ever have happened with its eruption of creative spirit, had it not been for tuberculosis? In general, is creativity ever possible without the feeling of malady and dis-ease? In ancient Greece, the sick headed for an asclepeion, a healing temple to the god Asclepius, to find cure for their maladies. In the nineteenth century, it was in the sanatoria typically located in high mountains, where TB patients sought refuge and hope. There they were ordained to take plenty of rest, inhale fresh mountain air and partake proper nutrition. However, before antibiotics were invented the statistics were very grim: around seventy per cent of patients died in the sanatoria. Those who recovered were not seriously ill in the first place. This was also true for the prestigiously located Davos, where dying patients were carefully hidden in order not to ruin the reputation of the resort. Only the rich could afford a curative stay on the Alpine heights. It is worth remembering, however, as Mary Dobson put it, that “the disease hit hardest at those whose lives were blighted by poverty and poor nutrition, and worked in badly ventilated, overcrowded, cold, damp or dusty conditions.” To this day TB remains a disease of the poor and the dispossessed, the ones who are easily forgotten, unlike the high profile figures of the Romantic period.

Constance Markievicz, “Visit To A Dublin Family During Thetuberculosis Epidemic”

The first sanatorium was built in Davos by Alexander Spengler, who also invented the famous “corpse rest” (Kadaverruhe in German).

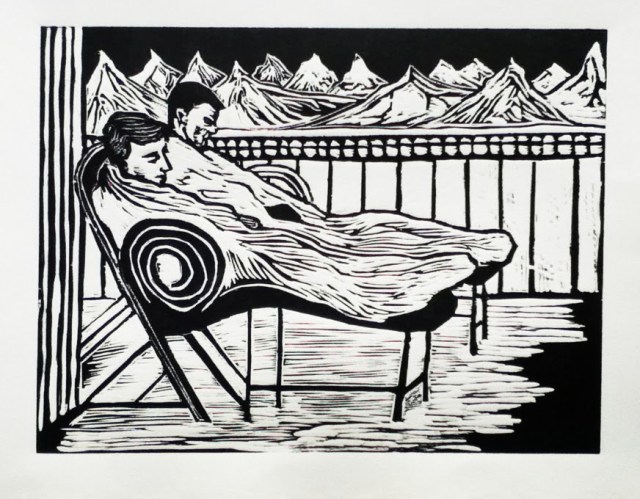

Patients were advised to swaddle in warm blankets and spend hours inhaling ice cold mountain air under the beams of the sun. This procedure was beautifully and memorably described by Thomas Mann in The Magic Mountain. Its hero Hans Castorp comes to Davos “only for two weeks” to visit his cousin, but ends up staying in the sanatorium for seven years after he is also diagnosed with consumption. Thus begins his journey of self-discovery, which leads him to the understanding that to be truly and deeply human is to be frail, to suffer and always remember about death. Or as one of the characters puts it, “to be human was to be ill.” In his Reader’s Guide to Mann’s novel, Rodney Symington quotes the echoing famous words from Beckett’s Endgame: “You’re on earth; there’s no cure for that.” A different sort of consciousness opens with such a realization: one aware of things infinite and ultimate – a mythical understanding of life. The title of the novel came from a passage in Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy: “Now it is as if the Olympian magic mountain had opened before us and revealed its roots to us” (quoted after Symington). Like the World Tree, the magic mountain has its roots planted in the dark earth while its branches reach high to the sky.

Hans Castorp was a conventional young man, a member of the affluent bourgeoisie with a robust work ethic. This conventional way of life, however, did not offer him any fulfillment:

“Hans Castorp respected work… Work was for him, in the nature of things, the most estimable attribute of life;

…

Exacting occupation dragged at his nerves, it wore him out; quite openly he confessed that he liked better to have his time free, not weighted with the leaden load of effort; lying spacious before him, not divided up by obstacles one had to grit one’s teeth and conquer, one after the other.”

Given the luxury and freedom of time in Davos, Hans Castorp flourished. In a secluded magical shrine of the Alpine valley he was simultaneously made us acutely aware of his own frail body and of his inner spirit. The infinite vistas of contemplation opened to him, accompanied by an aching, fleshy desire for a fellow convalescent – Clavdia Chauchat. In my absolute favorite passage Hans muses over the meaning of life:

“What then was life? It was warmth, the warmth generated by a form-preserving instability, a fever of matter, which accompanied the process of ceaseless decay and repair of albumen molecules that were too impossibly complicated, too impossibly ingenious in structure. It was the existence of the actually impossible-to-exist, of a half-sweet, half-painful balancing, in this restricted and feverish process of decay and renewal, upon the point of existence. It was not matter and it was not spirit, but something between the two, a phenomenon conveyed by matter, like the rainbow on the waterfall, and like the flame. Yet why not material – it was sentient to the point of desire and disgust, the shamelessness of matter become sensible of itself, the incontinent form of being. It was a secret and ardent stirring in the frozen chastity of the universal; it was a stolen and voluptuous impurity of sucking and secreting; an exhalation of carbonic acid gas and material impurities of mysterious origin and composition. It was a pullulation, an unfolding, a form-building (made possible by the overbalancing of its instability, yet controlled by the laws of growth inherent within it), of something brewed out of water, albumen, salt and fats, which was called flesh, and which became form, beauty, a lofty image, and yet all the time the essence of sensuality and desire. For this form and beauty were not spirit-borne; nor, like the form and beauty of sculpture, conveyed by a neutral and spirit-consumed substance, which could in all purity make beauty perceptible to the senses. Rather was it conveyed and shaped by the somehow awakened voluptuousness of matter, of the organic, dying-living substance itself, the reeking flesh.

…

…the image of life displayed itself to young Hans Castorp. It hovered before him, somewhere in space, remote from his grasp, yet near his sense; this body, this opaquely ehitish form, giving out exhalations, moist, clammy; the skin with all its blemishes and native impurities, with its spots, pimples, discolorations, irregularities; its horny, scalelike regions, covered over by soft streams and whorls of rudimentary lanugo.”

Life came to Hans in the shape of Clavdia.

In the nineteenth century tuberculosis was called the robber of youth. In “Elgin Marbles” Keats wrote contemplatively:

“My spirit is too weak—mortality

Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep,

And each imagined pinnacle and steep

Of godlike hardship tells me I must die

Like a sick eagle looking at the sky.”

Joseph Severn, “Keats’s Death”

The Romantics glorified consumption, associating it with beauty (especially in women), delicate spirit and heightened artistic sensitivity. The victims were perceived as innocent and holy. Nevertheless, the gruesome truth was that the disease totally ravaged the lungs of the victims, while the sheer amount of blood coughed up was often astounding. Still, George Sand insisted that Chopin coughed “with infinite grace” while Edgar Allan Poe described his dying wife Virginia as “delicately, morbidly angelic.”

Edvard Munch, “Angel of Death”

In one of the most beautiful short stories called “The Birch Grove,” a Polish writer Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz gives a more realistic portrayal of the disease, yet without losing its mystical aura. There, a young consumptive man arrives in the countryside “to die.” His elder brother lives there with his young daughter, both deep in mourning after his wife’s recent death. The young man, though extremely weak and in constant pain, is greedier for life than his healthy brother. Towards the end of the story, the older brother, similarly to Hans Castorp, experiences a mystical moment of connection with all life, while standing in the birch grove in the middle of the night. The white entangled trunks remind him of feminine arms pointing upwards as if in ecstasy. This is a moment of sensual awakening, embracing life as it is in the moment. It is natural that great writers think alike, but I find it quite extraordinary that Hans Castorp experienced a very similar epiphany looking at bare arms of Clavdia Chauchat during the Walpurgis-Night ball:

“Poor Hans Castorp! He was reminded of a theory he had once held about these arms, on making their acquaintance for the first time, veiled in diaphanous gauze: that it was the gauze itself, the ‘illusion’ as he called it, which had lent them their indescribable, unreasonable seductiveness. Folly! The utter, accentuated, blinding nudity of these arms, these splendid members of an infected organism, an experience so intoxicating, compared with that earlier one, as to leave our young man no other recourse than again, with drooping heed, to whisper, soundlessly: ‘O my God!’”

A sense of approaching end must render every moment acutely and piercingly real. Looking at John Keats death mask, it is hard not to wonder whether his awareness of the imminent death was instrumental in causing his talent to flower so passionately and frenetically in the last years of his life. Perhaps in a creative individual, life and talent intensify when confronted with death. And yet a creeping feeling of waste and of tremendous loss remains, beautifully expressed by Rilke in one of his Sonnets to Orpheus (translated by Edward Snow):

“Illness was near. Already gripped by shadows,

your blood coursed darker; yet, as if only fleetingly

suspicious, it burst forth into its natural Spring.

Again and again, amid darkness and downfall,

it flared earthly. Until after terrible pounding

it stepped through the hopelessly open gate.”

Keats – death mask

Sources:

Mary Dobson, Murderous Contagion: A Human History of Disease, Kindle edition

Rodney Symington, Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain: A Reader’s Guide, Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2011

Interesting. While I think “dis-ease” can aid the creative process at time, I don’t think it’s essential. I think shifting states of consciousness is important, and while that definitely happens to some people who suffer from physical decline, it also occurs through healthy meditation and moments of intense joy or pleasure. Have you read Huxley’s “Heaven and Hell”? Great essay about psycho-chemical changes that occur when the body is deprived of nutrients, or when in prolonged pain, that result in hallucinogenic visions, similar to those brought on through psychotropic drugs.

Well, coffee is ready. My brain needs a kick-start. 😉

Cheers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haven’t I mentioned I essentially grew up reading Huxley? Was really hooked at one point… just on reading, though.

I agree with your point about disease, Jeff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now that you mention it, I think you did tell me that at one time. Hard to remember everything at my age 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wunderbar erzählt, danke schön ☺❤❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks:)

LikeLike

Reblogged this on lampmagician.

LikeLike