The Inuit peoples have a profound connection to the Arctic as their ancestral homeland. Across the Arctic, one deity stands out as an all-powerful goddess of the sea and the underworld. Her name is Sedna. The name itself is an etymological mystery: some scholars refer to her as She Down There (1), others understand her name as “the one who is before,” i.e. the primordial goddess (2). Her myth is as chilling as the icy waters of the northern ocean.

Among many versions of the story, the one that appealed to me the most was retold by Andy Gurevich, who adapted it from Franz Boas, a nineteenth-century pioneer of anthropology. Sedna was a beautiful maiden, who did not want to marry. Yet eventually, she did marry a young suitor, who, however, turned out to be an evil bird-man. He had promised to look after her, but instead, he made her life utter misery. When her father found out about this, he killed the bird-man and took the daughter back home in his kayak. When Sedna and her father were crossing the rough sea, the other evil bird-men pursued them, trying to capsize the boat. In order to appease the angry spirits, the father threw Sedna overboard. He prevented her from climbing back into the kayak by cutting off her fingers with a knife. Her chopped off fingers turned into sea creatures such as whales, seals and fish. (3)

It is at this point that the myth usually ends. Sedna transforms into a powerful sea goddess. Subsequently, similarly to the Greek Demeter, when she is angry, she withholds the sea creatures, which means that the hunters come home empty handed. The starving community needs to send a shaman to appease her by combing her entangled hair.

Yet Gurevich continues the story. After the bird-men fly away, the father helps the daughter climb back into the kayak. Together they return to the village. But Sedna is full of resentment towards her father. When he falls asleep, she sends her dogs to devour her father’s hands and feet:

“Her father awakened in agony and hurled a curse upon himself, his daughter, and her dogs. To his surprise, the earth began to rumble with a low roar. And as it rumbled, it began to shake. At first it shook so that one might hardly feel it. But then it shook more and more violently. Suddenly, the earth gave way beneath their home, engulfing daughter, father, dogs, and tent. Down, down, down they fell into the land of Adlivun, the Underworld. There, Sedna became its ruler and the supreme power in the universe.” (4)

It is fascinating that the central deity in the Inuit myth is a mother goddess, not a sky god. I suspect this can be attributed to the sheer nature of Arctic life and its constant threats to survival. Sedna embodies the dual nature of the forces of nature—bestowing life and taking it away. It is a bloody creation myth that vividly portrays the fine line between life and death at the very origin of life. The motives of mutilation and dismemberment play a crucial role in the story. Like Osiris or Dionysus, Sedna is also mutilated. Yet unlike the masculine gods, who symbolically stand for unity, Sedna’s body is not restored to wholeness. She remains a creature of the underworld but also rules the multiplicity of life forms and also their imperfections, which sprang from the original primordial unity.

In his Dictionary of Symbols, Jean Chevalier points out that God delights in odd numbers, while our human civilization relies on even numbers and sees any kind of mutilation, be it mental or physical, as a disqualification. Chevalier says:

“The deformed, limbless and handicapped have this in common that they are marginalized by human or ‘daylight’ society, since their ‘evenness’ is affected, and must perforce now belong to the other order, that of darkness, be it celestial or infernal, divine or satanic.”

By virtue of synchronicity, I have just finished reading an extraordinary Polish novel by Joanna Bator. I have read it in my native Polish but now it has also become very successful in Germany and in Switzerland. Unfortunately, it has not been translated into English yet. I realized that the novel has a lot in common with the myth of Sedna. First of all, the central characters are all women while men are described as “craters” or “empty spaces” in their lives. The book embodies the quintessential aspects of femininity as an archetype. The novel prominently features a recurring motif of dismemberment. However, this time, it’s the women who carry out the gruesome execution.

This post was sparked by my first exhibition visit this year: “Sedna – Myth and Change in the Arctic” at the North America Native Museum in Zurich. The exhibition was truly worthwhile, notably due to the abundant collection of sculptures and paintings created by artists from Canada, Greenland, and various Arctic regions. Below you will find a selection of the exhibits with a commentary from the brochure, which accompanied the exhibition. The exhibition segment that focused on the forced Christianization and assimilation of the Inuit resonated deeply with me. Sedna’s story might parallel the sense of betrayal or loss experienced by some Inuit communities as their traditional beliefs and practices were marginalized or suppressed due to the imposition of Christianity. I was especially moved by this little sculpture:

It shows a homeless Inuit living in Canada, sitting on a slab of “concrete ice.” He looks hopelessly into a manhole.

Below are some more photos I took at the exhibition.

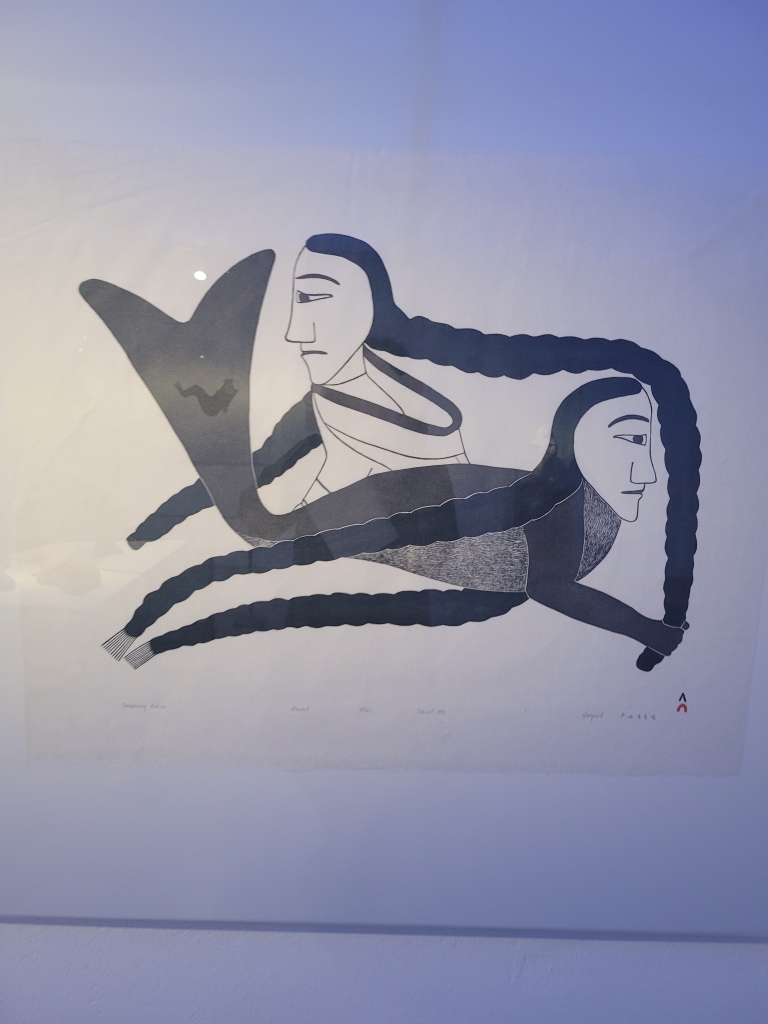

1993: the sea goddess Sedna

compares her braids to those of the

human Sedna

(Ningeokuluk); 2008 Sedna whispers something in the ear

of the woman with the traditional

facial tattoos. The most important

tunniit (tattoos) of a woman are those

on her face and hands. … The first tunniit, usually

on the chin, shows that the girl has

the necessary skills to take an active

role in the community and bear

responsibility.

Notes:

(1) https://mhcc.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/28/2021/02/ENG250_InuitMyth_History_Culture.pdf

(2) Wardle, H. Newell (1900). “The Sedna Cycle: A Study in Myth Evolution”. American Anthropologist. American Anthropological Association. 2 (3): 568–580. doi:10.1525/aa.1900.2.3.02a00100. JSTOR 658969

(3) https://mhcc.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/28/2021/02/ENG250_Sedna_Myth.pdf

(4) Ibid.

An interesting take on Sedna from the astrological perspective:

https://www.astro.com/astrology/aa_article190401_e.htm

Support my blog

If you enjoy my writing, please consider supporting my work. Thank you very much in advance.

$1.00

Sedna reminds me of Lilith with the bird-men/angels chasing after her.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting – that makes a lot of sense. They both experienced patriarchal rejection.

LikeLike