In Chinese mythology, the universe begins as a formless chaos or an egg. Inside this chaos is Pangu, a giant who eventually breaks out of the egg. As he emerges, he separates the chaos into yin and yang, which represent the fundamental dualities of existence. From these dualities, the world is formed, with yin and yang continuously interacting to create and sustain life. This is a common motif in many creation myths. From the primordial unity, consciousness emerges through the separation of opposites. This duality is mirrored in the division of the human brain into the left and right hemispheres.

C. G. Jung wrote in Mysterium Coniunctionis:

“Consciousness requires as its necessary counterpart a dark, latent, non-manifest side, the unconscious, whose presence can be known only by the light of consciousness.”

In his book The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, Iain McGilchrist argues that Western culture has been repressing the right hemisphere of the brain, resulting in a collective neurosis. He identifies an inherent conflict between the two hemispheres and notes that this conflict is intensified by a pronounced favoritism towards the left hemisphere. To use the terms from Jungian psychology, McGilchrist suggests that the Western collective ego has severed itself from its nourishing, unconscious roots.

McGilchrist’s book is written in a circular fashion: it is not a logical exposition but rather a circumambulation (moving around) of the topic. This cannot be an accident. Since the book’s aim is to restore the importance of the right hemisphere, the way it is written mirrors how the right hemisphere works. It is not linear but cyclical. It keeps circling back to issues it previously touched upon, deepening them each time.

Nowadays, a lot is said about the deficit of attention and the omnipresent distraction. I would argue that the current crisis is related to the subject of McGilchrist’ book. The right hemisphere represents broad attention. It sees things in their context, while “the left hemisphere sees things abstracted from context, and broken into parts.” (1) The right hemisphere, like the Jungian unconscious, explores the environment vigilantly and with care. What it brings to attention, can be processed and classified by the left hemisphere. Crucially, what the left hemisphere deals with is decontextualized, which means not embedded in the living world. It produces “abstracted classes of things” while the right hemisphere deals with “actually existing things.” Consequently, the left hemisphere is preoccupied with classes and abstract types while the right hemisphere concentrates on “the uniqueness and individuality of each existing thing or being.” To put is simply, the left brain prefers all things mechanical, while the right brain is drawn to life.

Only the right hemisphere can carry us to something new; only the right half of the brain can show us a new perspective and a new territory. The left hemisphere, in contrast, can be described as “self-referring.” While the left hemisphere follows a clearly defined agenda, the right one is more often to whatever may come; “it is vigilant for whatever is, without preconceptions, without a predefined purpose.” Towards the end of his book McGilchrist diagnoses our times as, unsurprisingly, dominated by the rational left hemisphere. As a society we do not value “the pre-reflective grounding of the self” – that is, the right hemisphere and what it represents. Without this grounding, we turn to over-stimulation to fight the ever-present boredom.

The two hemispheres of the brain perceive the body in fundamentally different ways. For the right hemisphere, the body is something we inhabit and experience directly. In contrast, the left hemisphere views the body as an object in the world, detached from personal experience. This distinction has significant implications for social interactions and our sense of self. The right hemisphere is responsible for forging social connections and seeking new experiences, constantly engaging with the world to build relationships. On the other hand, the left hemisphere tends to prefer “atomistic isolation,” focusing on individual parts rather than the whole. A sense of self can only truly emerge through contact with others, facilitated by the right hemisphere. Neurological damage to the right hemisphere often results in schizophrenic isolation and a disconnection from reality, highlighting its crucial role in maintaining social bonds and a coherent sense of identity.

Given that the right hemisphere’s domain encompasses life in all its messiness, it is no surprise that emotions and empathy also fall under its sphere of control. The right hemisphere deals with the expression of raw, warm and authentic emotions while the left hemisphere “specialises in more superficial, social emotions.” Furthermore, the left hemisphere is selfish and competitive; the right – cooperative.

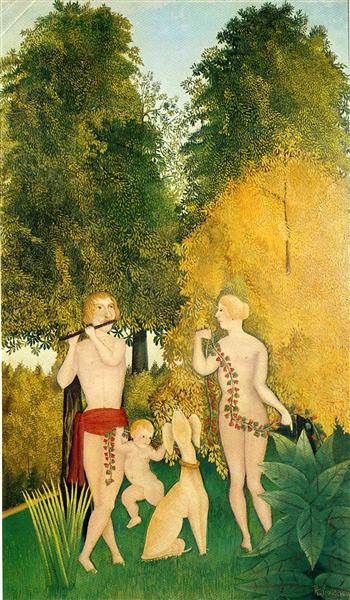

The “selfish” and “disconnected” left hemisphere values utility above all else. It strives to maximize gain and profit. It values a clear purpose. On the other hand, the right hemisphere plays a dominant part in those spheres of life, which are normally not valued by post-industrial societies, i.e. “imagination, creativity, the capacity for religious awe, music, dance, poetry, art, love of nature, a moral sense, a sense of humour and the ability to change …[one’s] mind.”

McGilchrist postulates the affinity between archetypes and symbols with the right hemisphere. He writes,

“.. a symbol such as the rose is the focus or centre of an endless network of connotations which ramify through our physical and mental, personal and cultural, experience in life, literature and art: the strength of the symbol is in direct proportion to the power it has to convey an array of implicit meanings, which need to remain implicit to be powerful.”

The left hemisphere understands only literal and explicit “signs”, for example the red traffic light.

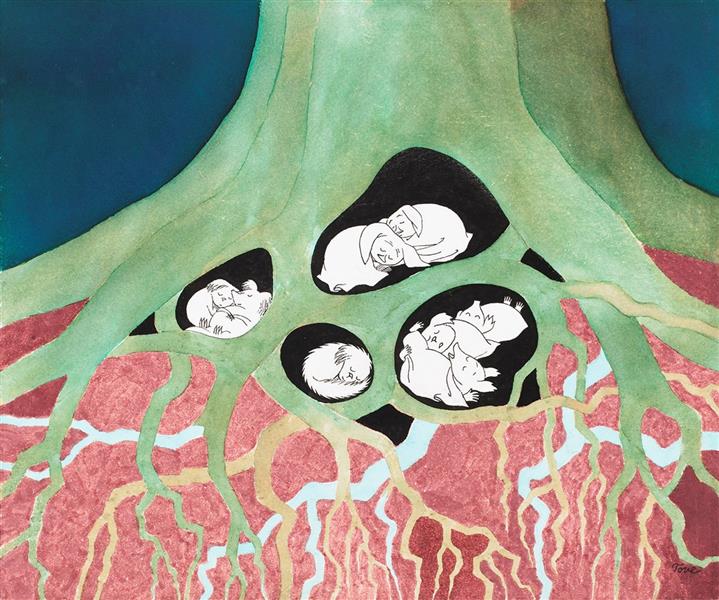

Crucially, Jung viewed archetypes and symbols as embedded in life, not abstract and lifeless. In his essay “Mind and Earth” Jung offered a definition of archetypes as “living and active foundations” of the psyche. He saw them as “the roots which the psyche has sunk not only in the earth but in the world in general.” Through the archetypes, “psyche is attached to nature” forming a tangible link with the earth and the body. (2)

The central metaphor of the book, that of the master (the right hemisphere) and his emissary (the left hemisphere) is based on the idea that the emissary has usurped the role of the master in our culture. The left hemisphere pretends to dominate the whole of experience. Yet in fact its world is fairly limited: it stays within its own closed loop of information. The knowledge it possesses is based on representation: it deals with things and ideas that it already knows: it has no access to the living world and to the actual “things” that it so eagerly talks about. It sees the world merely as a mechanism with parts that can be utilized or rearranged. It seeks to analyze, separate and divide. It seeks to exploit the world that it treats as “a heap of resources.”

The right hemisphere, however, sees the world as “a living thing.” McGilchrist goes as far as to say that the left, “bloodless” hemisphere is parasitic in relation to the right:

“It does not itself have life: its life comes from the right hemisphere… The left hemisphere is competitive, and its concern, its prime motivation, is power.”

In other words, the left hemisphere knows nothing of the soul. Not only that, it is also suspicious of the body. The same goes for nature, religions and any kind of spirituality; anything that depends on the implicit context for that matter. The despotic left hemisphere cannot stand all of these because they undermine its power. It loves talking about these subjects but only from a conceptualized standpoint:

“Today all the available sources of intuitive life – cultural tradition, the natural world, the body, religion and art – have been so conceptualised, devitalised and ‘deconstructed’ (ironised) by the world of words, mechanistic systems and theories constituted by the left hemisphere that their power to help us see beyond the hermetic world that it has set up has been largely drained from them.”

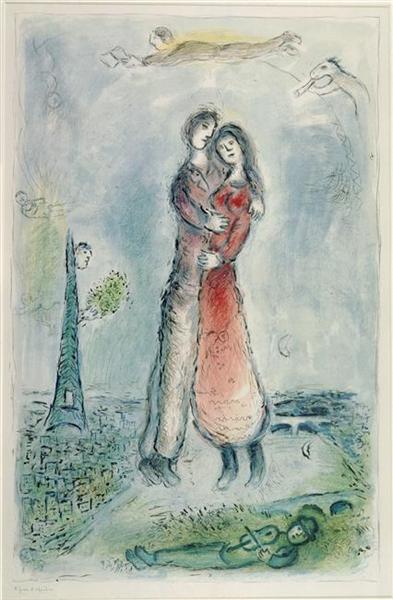

The main emotion of the right hemisphere, so distorted and repressed in our culture, is “a desire or longing towards something, something that lies beyond itself, towards the Other.” McGilchrist speaks of a relational nature of the right hemisphere. An important relationship is the one with the Absolute, be it a Deity, the Unconscious or the Lover. He draws our attention to the Sistine Chapel fresco that depicts God sending divine communication to Adam’s left hand, which means the one connected to the right hemisphere. McGilchrist emphasizes the right hemisphere’s connection to life, the embodiment but also to the realm of the archetypes. He explains his view of the archetypes and their connection with the right hemisphere in this particularly striking passage:

“He saw these as bridging the unconscious realm of instinct and the conscious realm of cognition, in which each helps to shape the other, experienced through images or metaphors that carry over to us affective or spiritual meaning from an unconscious realm. In their presence we experience a pull, a force of attraction, a longing, which leads us towards something beyond our own conscious experience, and which Jung saw as derived from the broader experience of humankind. An ideal sounds like something by definition disembodied, but these ideals are not bloodless abstractions, and derive from our affective embodied experience.”

It is precisely for this reason that the right hemisphere can have prophetic or divinatory qualities. Our world, however, being dominated by the left hemisphere, knows nothing of forces beyond its ken. We are busy, says McGilchrist, imitating machines while “skills have been downgraded and subverted into algorithms.”

McGilchrist offers a summary of the role the hemispheres play during different cultural epochs. Not surprisingly, the Renaissance brought the dominance of the right hemisphere. Especially the plays of Shakespeare celebrated the richness and variety of the human experience and life itself; “at every level he confounded opposites, seeing that the ‘web of our life is of a mingled yarn, good and ill together’” Ambiguity, nostalgia, soul longing were all squashed in the times of the Enlightenment. Descartes with his I think therefore I am wrote of a deep mistrust of the body, which in his view distorts the purity of reason. The light component in the Enlightenment meant shunning of the shadows. That changed when Romanticism came with its predilection for the right hemisphere. Suddenly moonlight, twilight, shadows, mist and fog were in, together with deep nostalgia, melancholy and longing for redemption.

In our left-hemisphere dominated times, technology and bureaucracy are in their golden age as perfect “systems of abstraction and control.” While the right hemisphere sees every individual as unique, the left one sees them as “simply interchangeable (‘equal’) parts of a mechanistic system, a system it needs to control in the interests of efficiency.” The right hemisphere accepts the imperfect, mortal human; the left one dreams of omnipotence and endless abstracted existence.

In a similar vein, C. G. Jung in The Red Book spoke about the dichotomy spirit of our times (Zeitgeist) and the spirit of the depths:

“The Zeitgeist considers dreams as ‘foolish and ungainly,’ and itself as filled ‘with ripe thoughts.’ It considers itself superior due to its developed logical-discursive thinking. It faces simple visual thinking with condescending disdain. This thinking in the mode of the Zeitgeist is dominant, anticipatory, abstract, and self-confident. It is thinking in the style of scientifically methodical knowledge, or absolutized “directed thinking’…” (3)

In Grimm’s fairy tales, there is often a character who can be described as a “wise simpleton,” such as Hans Dumb and many others. Paul Brutsche contrasts the instinctive wisdom of these “dumb” characters with the know-it-all attitude of their older siblings. (4) Yet, in the fairy tales, it is Hans Dumb who marries the princess, symbolizing the attainment of inner wholeness. If our civilization does not learn to trust the “dumb, silent” hemisphere of the brain, we will continue to live in fragmentation and randomness.

Notes:

(1) McGilchrist, Iain. The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. Yale University Press, 2009.(all quotes, unless otherwise indicated, come from this book)

(2) The Collected Works of C.G. Jung: Vol. 10. Civilization in Transition, par. 53

(3) Paul Brutsche. “The Creative Power of Soul: A Central Testimony of Jung’s Red Book” in: M. Stein and T. Arzt, Jung’s Red Book For Our Time: Searching for Soul under Postmodern Conditions Volume 3. Chiron Publications, 2019.

(4) Ibid.

Support my blog

If you enjoy my writing, please consider supporting my work.

$1.00

.jpg)

It is interesting that all these writers ignore the cerebellum, that processes vision and proprioreception AND has as many neural connections as both frontal lobes combined.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting. Unfortunately, I do not know much about it and the book does not mention it; it only discusses the role of the corpus calossum.

LikeLike

Yes, the function and importance of the cerebellum is usually totally overlooked.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Relevant, as ever …

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree, especially with the advent of AI. Thank you

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m about three quarters through the book.

Enjoyed your reflections Monika!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, dear Debra.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You might add “Siddhartha’s Brain – Unlocking the Ancient Science of Enlightenment” by James Kingland, and

“No Self, No Problem How Neuropsychology Is Catching up to Buddhism”

by Niebauer, Chris

to your “to read” list.

Both fascinating, and on very similar topics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much. I will definitely take a look at both.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A wonderful read. I have been reading The Red Book with a group every Wednesday and I love dream states for messages … also started doing art with watercolours in February which is balancing me out!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I am glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the writing you do!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Sometimes it is so hard to find the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful article. I love these themes. Thank you for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Danah. I appreciate it especially because it took forever to write. It is an enormous book and so dense.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your effort shows, I really admire you! You are my favourite blog since forever, I am very grateful for your time and everything you share with all of us. Always looking forward to reading you and learn from you! Jai Ma!

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you Monika, an excellent piece with wonderful art accompanying it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Susan

LikeLike

Brilliant..!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much!

LikeLike

You might add to your reading list the late Leonard Shlain’s masterpiece The Alphabet Versus The Goddess. He covers many time periods and cultures who were exposed to writing which energized the left hemisphere of the brain, and led to the devaluation of everything that the right brain governs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much. I have heard of the book but I have never read it.

LikeLike