I. “The mother is the first world of the child and the last world of the adult. We are all wrapped as her children in the mantle of this great Isis.”

Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 9 (Part 1): Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious; par. 175

II. “Principle and origin of all things

Ancient mother of the world,

Night, darkness and silence.”

Mesomedes

I have recently come across a fascinating article in The Atlantic. It was written by Katharine Hillard and contains a number of claims about the symbolic meaning of the Black Madonna. I have grappled with the same question for a number of years now and have myself written a few blog posts on the subject, most recently here: https://symbolreader.net/2021/12/30/black-madonna-an-icon-of-mystery/

The assertion that the Black Madonna’s cult has pagan origins was familiar to me. But a few thoughts on why the ancient gods and goddesses were black did give me pause. She writes:

“We find in all the histories of mythology many instances where both gods and goddesses are represented as black. Pausanias, who mentions two statues of the black Venus, says that the oldest statue of Ceres among the Phigalenses was black.(1) Now Ceres, like Juno and Minerva, like the Hindu Maia and the Egyptian Isis, stood for the maternal principle in the universe, and all these goddesses have been thus represented.”

Regrettably, the article lacks references, rendering certain information challenging to verify. Intuitively, I appreciate the correlation she draws between the interchangeable use of dark blue and black in ancient depictions of gods and goddesses. I am persuaded by the symbolic connection she postulates between the fecund darkness of the night, the life-giving depths of the ocean, and the rich blackness of the soil:

“The basic idea of the productive power of Nature, giving birth to all things without change in herself, underlies every conception of the Virgin Mother; and behind the earthly form of Mary, the mother of Jesus, we can trace the grand, mysterious outlines of the Universal Mother, that Darkness from whence cometh the Light, that chaotic Sea that produceth all things. Water, as referred to in such allegories, is, of course, something quite different from the element we know, and represents that primordial matter whose protean shape so constantly eludes the grasp of science.”

But perhaps the most inspiring part comes towards the end of the article:

“In the mystic philosophies, darkness was also used as the symbol of the Infinite Unknown. Light, as we recognize it, being material, could be considered only as the shadow of the divine, the antithesis of spirit, and the Self-Existent, or Light Spiritual, was therefore worshiped as darkness.”

This is a very inspiring fragment, which reminds me of Meister Eckhart, who said that the divine essence is shrouded in darkness. This also ties in with the idea of “deus absconditus” – the hidden, unreachable God, the impenetrable Mystery above all mysteries. The Black Madonna remains hidden, mysterious, and beyond the grasp of the intellect. Like the Kabbalistic Ein sof, which refers to the infinite, unbounded, and unknowable aspect of the divine, she is also endless and beyond understanding. She is the source of all existence yet she remains hidden behind the veil. Hers is the hidden light, reminiscent of what the alchemists called lumen naturae (the light of nature).

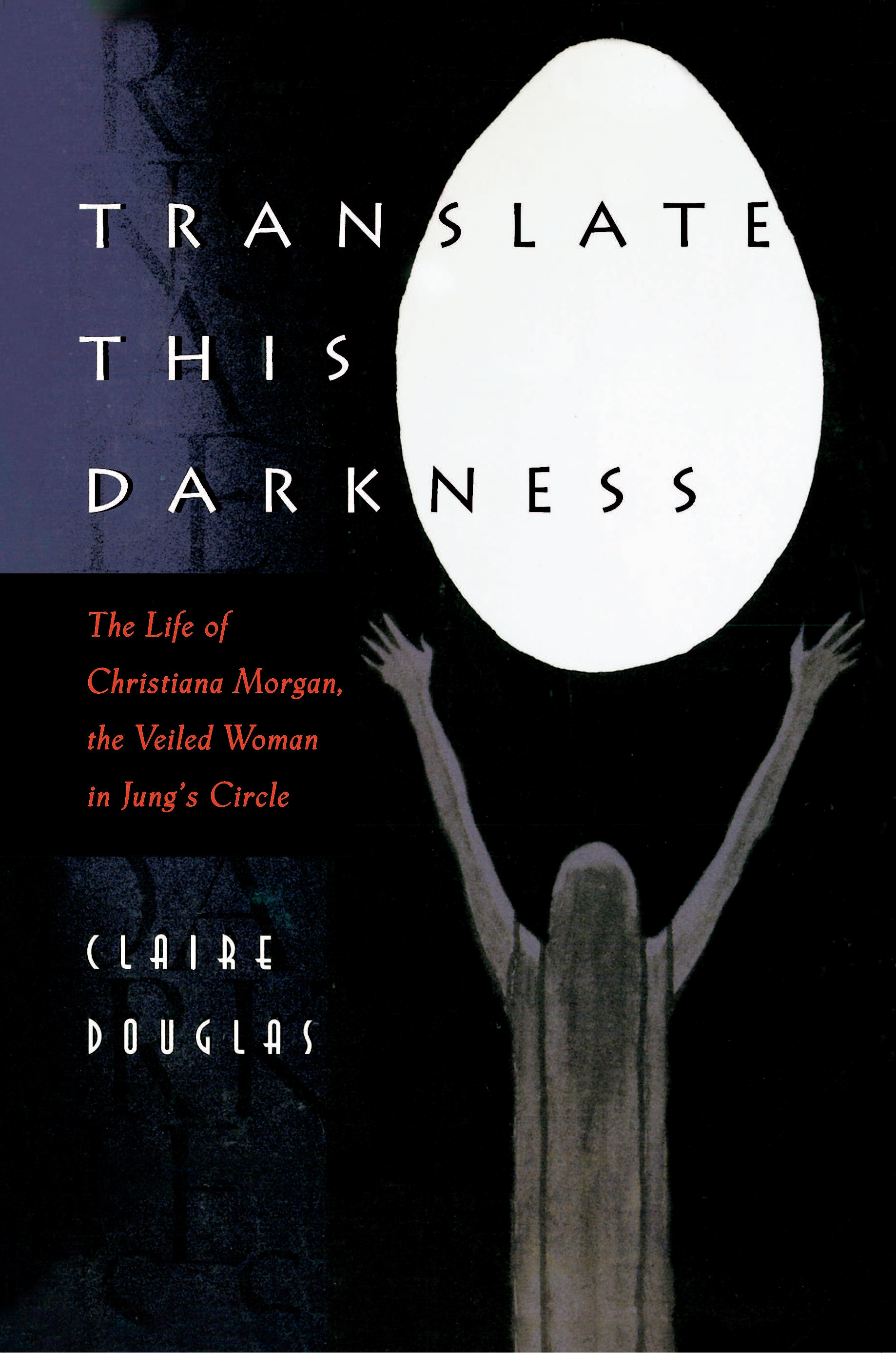

Odilon Redon’s print, which I included at the top of this post, draws its inspiration from Plutarch’s treatise, “On Isis and Osiris.” In this work, Plutarch recounts a temple in Sais where a statue of Isis stood, adorned with an inscription that read, “I am all that has been and is and ever shall be, and no mortal has ever lifted my veil.” Interestingly, some three centuries later, Proclus appended another line to this enigmatic inscription, “The fruit of my womb was the sun.” The inscription essentially attributes the birth or creation of the sun to Isis, symbolizing her as a divine and creative force in the universe; the invisible (veiled) source from which emanates the material world.

Much like darkness, the veil also functions symbolically as a means of concealing. The French philosopher Pierre Hadot devoted an entire book to the symbolism of the Veil of Isis and to a single verse from Heraclitus of Ephesus: “Nature loves to hide.” (2) Heraclitus was a devotee of Artemis of Ephesus, who in later times was frequently merged with the goddess Isis. He is believed to have reverently placed his writings within the sacred confines of the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus.

Hadot weaves the symbolism of Nature’s tendency to hide on 300 pages of his book. I could not help but ponder that much of his musings could be linked to the boundless symbolic depth of the Black Madonna.

Firstly, Hodot observes that concealment bears a profound connection to mortality, with the earth shrouding the body and a veil covering the head of the deceased. This resonated with the way Stoic philosophers saw nature: as the mother goddess of all things, who brings both life and death.

Seneca, a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, wrote, “What the principle is without which nothing exists we cannot know.” This sentiment underscores the profound humility that characterized Stoic philosophers in their contemplation of the mysteries of existence. Hadot expands on two ways of approaching Nature’s secrets. The Promethean way is bold; it tears the secrets from Nature’s bosom. This is predominantly our modern way. Conversely, the Orphic way is inspired by reverence towards the mystery; it approaches Nature’s secrets through song, art and poetry. The Age of Enlightenment and the era of industrialization ushered in a perspective that sought to penetrate the veil of nature, perceiving it solely as inert, non-sacred “matter” to be exploited. The connection of the word matter with mother was certainly lost on them.

Although a son of Enlightenment, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had some critical views of certain aspects of Enlightenment thought, particularly its materialistic and reductionist tendencies. Goethe spoke of the silent, symbolic language of nature, which he juxtaposed with the useless and idle chatter of human discourse. Says Hadot:

“Goethe affirms that the symbol … insofar as it is a form and an image, lets us understand a multitude of meanings, but itself remains ultimately inexpressible. It is ‘the revelation, alive and immediate, of the unexplorable.'”

This precisely captures my sensation when confronting the enigmatic depths of the Black Madonna. The profound significance is readily intuited, radiating forth, yet it defies verbal articulation. It is a symbolic, silent presence.

Hodot proceeds to discuss Goethe’s poem “Great is the Diana of the Ephesians,” which is a rejection of the “formless” God of Christianity and the embrace of the full-bodied goddess of Ephesus. For Goethe, says Hadot, “God is inseparable from Nature; that is, he is inseparable from the forms both visible and mysterious, that God/Nature constantly engenders.” Similarly, from my perspective, the symbolism of the Black Madonna rests firmly on the acceptance of the body and the physical world as sacred and divine.

Athanasius Kircher, a seventeenth-century German Jesuit scholar and polymath, interpreted the veil of Isis as a symbol of the secrets of Nature. The secrets that hide behind the veil (or behind the dark countenance of the Black Madonna) were described by Goethe as “Ungeheures,” which, as Hadot explains, is “an ambiguous term that designates as much what is prodigious as what is monstrous.” Goethe likened nature to the Sphinx while Kant wrote that “we can approach nature only with a sacred shudder.” The initiation bestowed by the Black Madonna is a similar mixture of trembling and awe.

The final part of Hadot’s book draws on the philosophy of Nietzsche, for whom Nature contains “the knowledge of depth”, and “a transcendence of individuality.” Hadot summarizes further:

“Man must therefore abandon his partial and partisan viewpoint in order to raise himself up to a cosmic perspective, or to the viewpoint of universal nature, in order to be able to say an ecstatic yes to nature in its totality, in the indissoluble union of truth and appearance. This is Dionysian ecstasy.”

It is a simultaneously simple yet profoundly unsettling notion: as integral parts of Nature, as bodies encompassed within the body of the Dark, Earthly Goddess of Nature, we bear the same unfathomable and disquieting secrets within us. Nietzsche, in his quest to transcend individual perspective, encountered madness. There is a peril associated with attempting to unveil the mysteries hidden behind the veil of Isis, as even Orpheus discovered at a cost. The captivating face of the Black Madonna stands as the guardian of this eternal paradox.

Notes:

(1) She refers here to the inhabitants of Phigaleia; perhaps a correct term would be “Phigal(e)ians”; compare Pausanias’ Description of Greece https://www.gutenberg.org/files/68680/68680-h/68680-h.htm. In Arcadia Demeter had the epithet Melaina – Black. In that connection Pausanius mentions a cave sacred to Demeter:

“The second mountain, Mount Elaius, is some thirty stades away from Phigalia, and has a cave sacred to Demeter surnamed Black.”

(2) Pierre Hadot, The Veil of Isis: An Essay on the History of the Idea of Nature, translated by Michael Chase (Cambridge, MA & London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006)