This post is an attempt at a symbolic reconstruction of a movie I have seen recently. After seeing it, I was so deeply moved that I immediately rewatched it and proceeded to jot down hurriedly ten pages of notes and impressions that it spurred me to. The movie is called The Eight Mountains (2022) and was co-directed by Felix van Groeningen and Charlotte Vandermeersch. My post is going to contain a lot of details relating to the plot, so if you would like to discover “what happened” on your own, you have been warned.

This is a summary of “what the movie is about” that I found on the website of the British Film Institute:

“It’s 1984 when Pietro … first arrives in the Italian Alps for a summer holiday with his mother…. At his first meeting with Bruno, the difference between the pair is stark. Pietro is a soft-spoken 11-year-old in bright woolly jumpers and shiny hair; Bruno …, slightly older, is all wellies and cow muck. … Bruno is foul-mouthed and has to interrupt their play to milk the cows. They literally speak different languages as Bruno teaches Pietro the dialect of the village where he is the only remaining boy, everyone else fleeing in the face of an economic reality that has made rural life untenable.

Despite the idyllic setting, …, the friendship has its complications. The boys both have dysfunctional relationships with their fathers, and Pietro feels some jealousy when his parents appraise Bruno’s situation and try to take him back to Turin for schooling. When this falls through, the boys grow distant.”

This premise of the story reminded me of the friendship between the “civilized” Gilgamesh and the wild Enkidu, where Enkidu’s connection with the natural world and his more instinctual nature provide a contrasting perspective that influences Gilgamesh’s growth and development throughout the epic. When the parents want to take Bruno to the city Pietro is outraged and says: “A city will ruin a person like Bruno!” Much later, when they are both older in a moment of self-reflection Bruno describes himself as a wild man: one third man, one third beast and one third tree. Bruno is in the heart of the story: all characters define themselves in relation to him. He symbolizes the part of the soul lost or repressed in the modern world: the wildness of nature.

With one caveat, though. When the adult Pietro brings his city friends to the Alpine village to meet Bruno, one of the friends expresses his wonder of the unspoilt nature in the mountains. Bruno retorts: “It’s just you from the city who call it nature. It’s so abstract in your mind that even the name is abstract. Here we say woods, pastures, river, rock, path.” The groundedness of direct experience stands in start contrast to intellectual abstractions.

The mountainous regions have a true symbolic power. C.G. Jung spoke of solemnity of the mountains as a place where God’s work is done. The lush valleys stand for the horizontal dimension: this is where things are born, where flowers grow, where the rivers flow and the animals graze. As the Dalai Lama expressed it in a letter to Peter Goullart, “Soul is at home in the deep, shaded valleys.” In contrast, mountain peaks crown the vertical axis. Here the soul is drawn to the divine. As the Dalai Lama puts it, “Spirit is a land of high, white peaks and glittering jewellike lakes and flowers.” Here life is solitary. As the movie progresses, Bruno leaves his higher place more and more reluctantly. The mountain claims his soul. His roots are so strong that he cannot be moved any more.

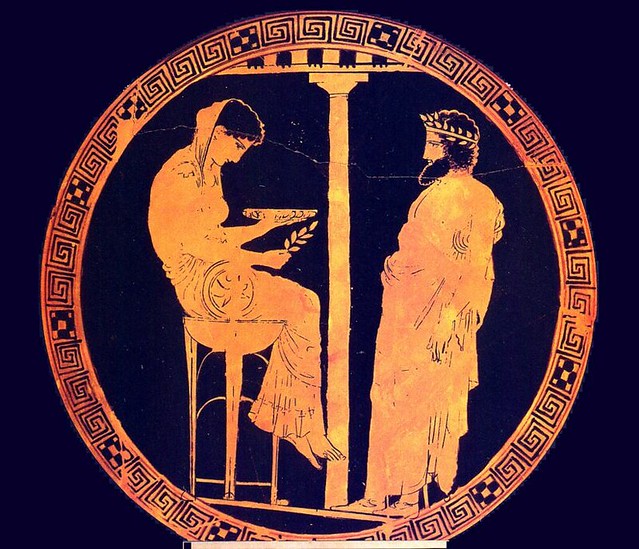

The central metaphor of the movie is that of the eight mountains. Pietro hears this myth on his journey through Nepal. The mount Meru (or Sumeru) is the cosmic mountain, which Eliade referred to as “the earth’s navel, the point at which the Creation began.” It is the source of creation, where Brahma the Creator dwells. Located at the centre of the universe, Meru “is a vertical shaft which links macrocosm with microcosm, gods with men, timelessness with time.” (1) Meru is thus “a preeminent motif for mandala symbolism.” (2) Its centre points both upward to divinity and inward – to the individual soul. The rest of the world revolves in constant twirls but the centre is always immovable.

While Pietro travels through Nepal in a later part of the story, he gets asked by the locals if he is making the tour of the eight mountains. This is directly connected to the Nepalese legend of Eight Mother Goddesses (Ashta Matrika), who are believed to reside on eight mountain peaks that tower over the Kathmandu Valley. It is believed that these eight mountains surround the cosmic Mount Sumeru. Pietro tells Bruno the myth and asks him, who learns more – the one who has seen eight mountains and eight sees or the one who has reached the top of the Mount Sumeru. Bruno understands immediately that he is the one who does not ever move from the holy mountain while Pietro has been making the tours of the eight mountains. Pietro, who at some point says, “I was tired of the old me. I wanted to transform, evolve, leave” is the one who is on the move while Bruno remains, strengthening his roots more and more with the coming years. He and his place on earth become inseparable.

A central motive in the story is the father complex that Pietro embarks on healing. Pietro’s father had a dream of building a house high up next to the peak of Mount Grenon (the name is fictitious but the movie was shot in Italy in the Aosta Valley). After amassing a pile of rocks from an ancient wall, the father suddenly passes away, leaving Bruno with the solemn pledge to construct the house in his memory. Pietro is shocked upon discovering that his father had kept in touch with Bruno and that they both had been climbing the mountains in Bruno’s village. Dejected, he says, “I inherited a ruin, a pile of rocks.”

Pietro also discovers a map left by his father, where he marked the trails they had walked in different colours. Pietro decides to walk all of these trails himself and carefully takes the time to add his mark on the map, too. He literally follows in his father’s footsteps and muses, “I lost my first father, who was a stranger to me, and found the second father – the father of the mountains.” On each peak that he climbs he flips through a summit book, where climbers note down the thoughts they had on the peak together with their names and the date of the climb. He reads all the words left by his father as a sort of a last message to him.

Perhaps the most touching and beautiful aspect of the movie is the friendship between Bruno and Pietro. When they were children, Bruno called Pietro Berio, which in his dialect meant “rock” as Pietro’s name also ultimately derives from the Greek petra (rock). And quite literally, although they lose touch for some time, they are both each other’s rocks. Together they undertake a project of building a mountain shelter to fulfil the dream of Pietro’s late father. They call the hut Barma Drola, which in the local dialect means “a protrusion in the rock, the ‘shelter’ you squeeze into during a storm in the mountains. (3) It is a refuge away from the world, where they both meet every year to renew their friendship. It is so close to the cosmic mountain that at some point the mountain claims it back to its womb. When Bruno dies, Pietro makes the decision never to return to the mountain again. He chooses the horizontal path, the path of life and incarnation. Bruno chose the path of ascension and had become one with the spirit of the mountain.

At the end of the movie Pietro becomes a writer and moves to Nepal, where he marries. During their last meeting at Barma Bruno says to Pietro, “I’m glad you have found your words.” As the son of the mountain, Bruno helps all the main characters to get in touch with their soul, to evolve towards their true essence. In this way, he takes upon himself the mantle of the sage or even the guru. I have found it quite fitting that alongside the 108 auspicious beads, each mala has a larger bead called Sumeru or Meru, which holds the mala together. It is also called the guru bead. Bruno is the guru bead of this beautiful story. He is the living, beating heart that not only sustains the story but also serves as a transformative force, breathing life into every character, infusing them with his wisdom and vitality. He functions as a guiding guru, shaping and inspiring the growth of each character within the narrative.

Notes:

(1) Mabbett, I. W. “The Symbolism of Mount Meru.” History of Religions, vol. 23, no. 1, Aug. 1983, pp. 64-83. Published by The University of Chicago Press.

(2) Ibid.

(3) https://www.lovevda.it/en/database/22/room-rentals-chambres-d-hotes/brusson/a-barma-drola/9003893

Support my blog

If you enjoy my writing, please consider donating to support my work. Thank you in advance.

$1.00

That sounds really intriguing! Especially your comparison with Gilgamesh and Enkidu. Thank you for this introduction. With my best regards, Aladin.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Aladin 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person