“Little good will come to you from outside. What will come to you lies within yourself. But what lies there!”

C.G. Jung, The Red Book, chapter XVIII (Liber Secundus)

Chapter XVIII of Liber Secundus is called The Three Prophecies. The title itself poses an important question of whether The Red Book is prophetic. In a book of dialogues dedicated to The Red Book by James Hillman and Sonu Shamdasani, the latter offers the following reflection:

“He [Jung] realizes around about 1917 that the prophetic tone, the prophetic language in which he wrote the first two sections of the text were given to him by this figure of Philemon, in other words, there’s a prophetic voice in him that is not himself. The issue then is one of differentiating being instructed by it without identifying with it. He did have a real career choice. He could have set up shop like Rudolf Steiner around the corner in Dornach and said, ‘This is the new revelation.’ I mean, gurus are two a penny in Europe in the 1920s—prophets of the new age, competing for the same clientele. He could have done that. But what then is interesting, what makes Jung Jung is, in a certain sense, the fact that he doubts his own visions and is more interested in the vision-making function than simply proclamation.” (1)

Jung chose the path of experience. He chose not to identify with the divine presence that was bestowing revelations on him. In a letter to Frau Patzelt, which Jung wrote in 1935, he emphasizes his reservations even more decisively:

“I have read a few books by Rudolf Steiner and must confess that I have found nothing in them that is of the slightest use to me. You must understand that I am a researcher and not a prophet.”

Though Jung touched the eternal in the experience that he described in Liber Novus, he decided not to proclaim it as the absolute truth. He decided against publishing The Red Book.

Chapter XVIII begins with a vision that Jung experienced on 22 January 1914, which he recorded in his black book. The soul asks Jung if he will accept whatever she brings to him without judgement or rejection. He agrees. The soul dives through the ages of humankind bringing him the worst atrocities: the annihilation of whole peoples, war, epidemics, and all kinds of “frightful feral savagery.” Jung accepts everything as gifts of the soul. But when the soul brings the treasures of all past cultures and “books full of lost wisdom,” he seems overwhelmed. No person can accept such an enormous wealth. It is wise to limit oneself and with contentment and modesty cultivate one’s own garden. Jung says:

“A well-tended small garden is better than an ill-tended large garden. Both gardens are equally small when faced with the immeasurable, but unequally cared for.”

The soul also brings Jung three prophecies – “ancient things that pointed to the future.” These are “the misery of war, the darkness of magic, and the gift of religion,” which all share the same capability of both unleashing and binding the forces of chaos. Before the First World War erupted Jung had had an overpowering vision of a flood that covered all Europe but was stopped by the Swiss Alps. He saw the sea of blood and a civilization turning into rubble. In the chapter that we are discussing Jung expresses the longing to know nothing because the memory of what he saw would not leave him alone. This is why it is so important, he claims, to keep a well-tended garden, because otherwise the depths of the collective unconscious, which contain everything, will swallow the individual. Therefore he declares that he wishes to discard “everything divine and devilish with which chaos burdened me.” He says that is is vital that an individual does not identify with the collective contents pressing upon the psyche:

“You should be able to cast everything from you, otherwise you are a slave, even if you are the slave of a God.”

Magic is the second gift that the soul brings Jung. In Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche (CW 8) Jung wrote that “’magical’ means everything where unconscious influences are at work.” (2) In the same volume he referred to psyche as “the greatest of all cosmic wonders.” (3) He also said further that “anyone should draw the conclusion that the psyche, in its deepest reaches, participates in a form of existence beyond space and time, and thus partakes of what is inadequately and symbolically described as ‘eternity.'” (4) But still he concluded that we would never be able to determine whether that was the absolute truth. From the perspective of the conscious mind, any proclamation as to the nature of the unconscious psyche is conjecture. When Jung says that “magic is dark and no one sees it” in the chapter of The Red Book that we are looking at, he is hinting at the occult nature of the unconscious psyche and its workings.

But even such hedged statements about the nature of the psyche did not win Jung any favours with scientists or scientifically minded psychologists of his time and of our time. Lance S. Owens makes an excellent point when he says that Jung was disowned not only by science but also by religion of his time. He explains:

“… both fields share a problematic blind spot: They both think that ‘religion’ stands against ‘the secular.’ However, the historical record shows that these two defined themselves not just against one another but, simultaneously, against a third domain…. This third domain that they both rejected has been referred to by different names, but the most well-known are superstition and magic.” (5)

Magic is the dark, shadowy domain inaccessible both to science and the institutionalized religion. It is religion which is the final gift that the soul bestows upon Jung. The Red Book seems to ponder an important question what religion will be like in the coming Aion of Aquarius. The main themes of the Aion of Aquarius have been summarized by Liz Greene as “the union of the opposites, the interiorisation of the god-image, and the struggle to recognise and reconcile good and evil as dimensions of the human psyche” rather than “projected duality of God and the Devil” that has been prevalent in the current Aion of Pisces. (6)

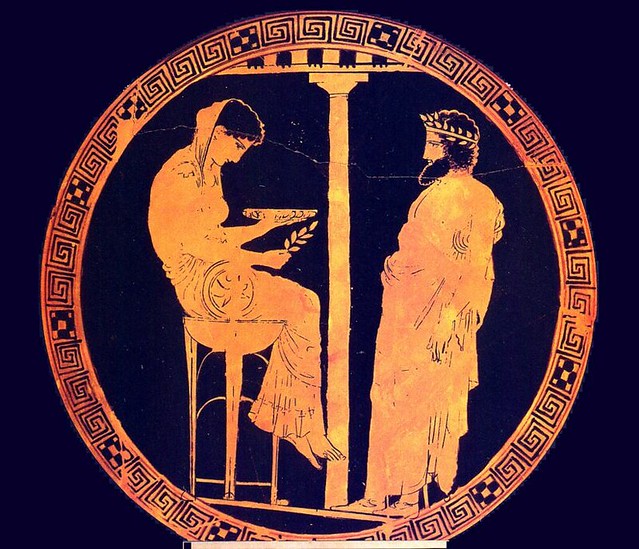

The chapter is accompanied by Image 125. In his invaluable footnotes Shamdasani explains that the scene depicted in the image resembles one of Jung’s childhood fantasies described in Memories, Dreams, Reflections. In it he imagined Basel to be a port and in his mind’s eye he saw a sailing ship on the waters of the Rhine. The image here shows Atmavictu in deep meditation (see part 30 for details about him). The Aquarian vessel on his head is being filled with divine prana or the water of the spirit, which emanates from the golden red solar mandala. It seems that the ship from the childhood fantasy sails on the border between divine and mundane reality. The orderly Swiss world below appears to be oblivious of the spiritual dimension depicted in the upper part of the image.

Notes:

(1) James Hillman and Sonu Shamdasani, Lament of the Dead: Psychology After Jung’s Red Book, Kindle edition

(2) par. 725

(3) par. 357

(4) par. 815

(5) Lance S. Owens, “C.G. Jung and the Prophet Puzzle,” in: Murray Stein and Thomas Arzt, editors, Jung’s Red Book for Our Time: Searching for Soul under Postmodern Conditions, volume 1, Kindle edition

(6) Liz Greene, “‘The Way of What is to Come’: Jung’s Vision of the Aquarian Age,” in: Murray Stein and Thomas Arzt, editors, Jung’s Red Book for Our Time: Searching for Soul under Postmodern Conditions, volume 1, Kindle edition

Support my blog

If you appreciate my writing, consider donating to support my work. Thank you very much in advance.

$1.00

Reading The Red Book – part 10

Reading The Red Book – part 11

Reading The Red Book – part 12

Reading The Red Book – part 13

Reading The Red Book – part 14

Reading The Red Book – part 15

Reading The Red Book – part 16

Reading The Red Book – part 17

Reading The Red Book – part 18

Reading The Red Book – part 19

Reading The Red Book – part 20

Reading The Red Book – part 21

Reading The Red Book – part 22

Reading The Red Book – part 23

Reading The Red Book – part 24

Reading The Red Book – part 25

Reading The Red Book – part 26

Reading The Red Book – part 27

Reading The Red Book – part 28

Reading The Red Book – part 29

Reading The Red Book – part 30

Reading The Red Book – part 32

Reading The Red Book – part 33

Reading The Red Book – part 34

Reading The Red Book – part 35

Reading The Red Book – part 36

Reading The Red Book – part 37

Reading The Red Book – part 38

Reading The Red Book – part 39

Pingback: Reading The Red Book (20) | symbolreader

Probably one of the best things I have read about Jung’s key decision to limit himself to scientific research rather than try to dive deep inito the endless eternal infinite mass of information held in the mass unconscious mind (the Akashic Field if you like).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, well put. Thank you very much.

LikeLike

How peculiar that I have kept an article from this website as a tab for months, and never went anywhere else here, but now that I decide to see what else is here the latest article is one about the precise chapter I have been ruminating over the last couple of days. Funny how these things happen!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This happens to me a lot but still amazes each time!

LikeLike

Pingback: Reading The Red Book (23) | symbolreader